Master Class

Learning the Basic Blackjack Strategy

By Don Schlesinger

For any serious blackjack player, learning the basic strategy of play (BS) is the first essential step on the road to becoming an accomplished player. And, over my long blackjack career, I have encountered dozens of players who profess to “know” basic strategy perfectly. It usually takes just three or four questions on my part to determine that, sadly, such is not the case.

For any serious blackjack player, learning the basic strategy of play (BS) is the first essential step on the road to becoming an accomplished player. And, over my long blackjack career, I have encountered dozens of players who profess to “know” basic strategy perfectly. It usually takes just three or four questions on my part to determine that, sadly, such is not the case.

The purpose of this article is twofold. First, I will present the correct basic strategy for a particular game that is very popular both in the U.S. and around the world. Then, I will offer a series of tips designed to make learning the BS as easy as possible. These mnemonics, or memory aids, have proven to be extremely helpful to countless numbers of players, and I hope you will find them useful. Let’s get started!

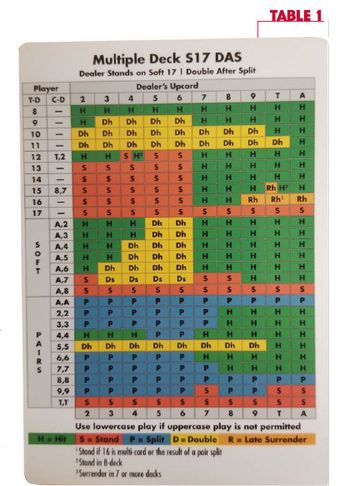

The color-coded chart you see in Table 1 is one of a dozen that are available in my series of Ultimate Blackjack Strategy Cards. It presents the correct basic strategy for a multiple-deck (typically, four, six or eight decks) game in which the dealer stands on all hands that total 17 (S17) and where doubling after splitting a hand (DAS) is permitted. It is important to understand that there is not just one BS that applies to all blackjack games. Rather, there is an entire collection of basic strategies that apply to games with different numbers of decks and different rules sets. The one below, therefore, represents one such correct BS.

As you look at the color-coded chart in Table 1, here are the several important points to observe and study, in this order of importance:

The Hard Hands

First, you will see, vertically, for the hands of 12 to 16, a big “dividing line,” or demarcation, separating the sea of red and the green section, on either side of the dealer’s upcards of 6 and 7. As a general observation, you do most of your standing, doubling and splitting when the dealer is vulnerable, with 2–6 upcards. Against 7–A, you hit much more frequently, and you double and split much less, as the dealer is more likely to make a hand of 17–21 and much less likely to bust, or break. As an example, the dealer breaks about 42% of the time when he shows a 5 or 6 but only 23% of the time when he shows a 10 and only 17% with a playable ace. So, your play reflects these facts. You stand more when the dealer has a low card, and you have to hit more when he has a high one, because if you stand with 12–16, and he busts only about 25% or less of the time, you will lose much too often if you stand.

You have to understand the logic of why you do things. This is all math. There are no hunches, guesses, sentiment, luck, etc. If you can’t play like a machine, you have no chance to ever become a good player. NONE! There is only one correct play for each hand, so there is no debate on the subject. This isn’t social studies or political science; you have to trust the math!

And so, you learn the hard hitting/standing plays first. They’re very simple. For any total of 8 or lower, always hit. For 9, 10 and 11, if you don’t double (see the section below), you always hit. With 12–16, stand vs. 2–6 (note the mnemonic in bold) and hit otherwise, with two exceptions: hit 12 vs. 2 and 3. Naturally, with hands of 17 or higher, always stand. That’s it!

Hard Doubling

Above, we mentioned totals of 9, 10 and 11. These represent the only three initial two-card holdings that do not contain an ace on which you should double. And again, the rules are quite simple: Double 9 vs. the dealer’s 3–6 (mnemonic: 9 = 3 + 6), otherwise, hit. Double 10 vs. 2–9 (10 to below 10), otherwise, hit. And double 11 vs. 2–10 (11 to below 11, the ace), otherwise, hit. Done! Soft Doubling

Next come the soft doubles. First, a definition. A hand is said to be “soft” if it contains an ace and cannot break with the addition of an extra card. So, A,5 or A,2,4 are soft hands, but A,3,9 is not, because although the hand contains an ace, the ace must be counted as one, and if you hit the hand (hard 13), you might break.

- The soft doubling rules are a bit more complicated, but if you look at the chart, you see, vertically, a kind of stepladder pattern. So, the doubling rules go like this:

- Double A,2 and A,3 vs. 5 and 6, otherwise hit. (2 + 3 = 5. Start doubling A,2 and A,3 vs. the 5.) Double A,4 and A,5 vs. 4, 5, 6, otherwise hit. (The mnemonic is apparent, no?)

- Double A,6 and A,7 vs. 3, 4, 5, 6. For A,6, if you don’t double, you hit.

- But A,7 is more complicated. You stand vs. 2, 7 and 8 but hit vs. 9, 10 and ace. This takes a little studying.

- For A,8 or higher, always stand.

By the way, NEVER call a hand such as A,7 “soft 18.” NEVER. It has nothing to do with 18. It’s ace- seven. You have to say it in your head that way. This is very important. If you are holding A,7, and I ask you what your hand is, do not answer “18, or soft 18.” It’s ace-seven. Period. The reason for my insistence is simple. I have seen untold numbers of players do nothing with A,7 but stand. They reason, erroneously, that they have 18 (they don’t; they have ace-seven!) and conclude that they must always stand with 18. They’re half right. You always stand with hard 18. This is different. And so, with A,7, sometimes you stand, sometimes you hit, and sometimes you double. Clear?

Pair Splitting

I feel that the memory aids below will be quite effective in helping you to learn when to split.

- Aces and eights, ALWAYS. (In other words, split aces and 8s against ALL dealer upcards.) Some

- will be familiar with the term “aces and eights” as the “dead man’s hand.” It’s the poker hand (pair of aces and pair of eights) that Wild Bill Hickok was holding when he was shot to death. But I digress.

- Fives and tens, NEVER. (NEVER split 5s or 10s vs. any upcard.) Some of you may be old enough to remember the name many of us gave to Woolworth’s: the 5 & 10. So, these are the Woolworth’s pairs. Don’t split them!

- Two, threes and sevens, vs. 2 through 7. (In other words, split 2,2, 3,3, and 7,7 vs. the dealer’s 2–7.)

- Fours vs. 5, 6. (Remember: 4, 5–6.)

- Sixes vs. 2–6 (Remember: Sixes to the 6.)

- Nines vs. 2–9, except vs. 7. (Remember: Nines to the nine. Split 9,9 vs. all dealer upcards 2–9, except 7. So, you stand vs. 7, 10 and Ace.)

I mentioned that understanding why you make certain plays can also help you to memorize the plays themselves. Here are a few explanations for some of the pair splits we’ve just considered. We always split aces because a starting hand of 2 or 12 isn’t very attractive (!), while starting with two hands of 11 is just great. We split eights for a very different reason. When the dealer has a low card, splitting is considered an offensive play. It permits us to break up the awful hand of 16 and replace it with two starting hands of 8, which, more often than not, get the money against the dealer’s low upcards. And, while usually not providing us with winners, the two eights are, nonetheless, the better alternative vs. high dealer upcards than starting with our dreadful 16.

We never split fives because the starting hand of 10 is an excellent one, while beginning with two hands of five would be a very poor choice. And, of course, we don’t split tens because even though beginning with two hands of 10 each is a winning scenario, keeping the two tens together and beginning with one hand of 20 is the far superior alternative.

Finally, we split nines (except vs. 7) all the way to the dealer’s 9 because, although 18 is sometimes a winning hand, beginning with two nines is the more attractive move. And, while some may find it counterintuitive to split nines vs. the dealer’s 9 (novices virtually never make this move), the logic is clear-cut. Your 18 is actually an 18% net loser vs. the dealer’s 9. Split, and each 9 is only a 4% loser, so you lose 8% overall. Therefore, splitting is 10% better than standing.

Surrender

A favorable rule for the player, surrender permits you to give up half of your initial wager in exchange for not playing out your hand. The dealer takes half your bet, removes your cards, and you’re done for that round. Since you lose 50% of your wager, you should surrender only those hands whose overall expectation is to lose more than 75% of the time (if you lose 75%, you win 25%, and 75% minus 25% is 50%). There are only four starting hands so poor as to meet this criterion: 16 vs. dealer’s 9, 10 or ace, and 15 vs. dealer’s 10. So don’t become “surrender happy.” Many novices over-surrender and start throwing away virtually any stiff hand. Follow the strategy. Stay disciplined.

Insurance

Here’s the easiest rule of all: Don’t ever take insurance. Even if you have a blackjack, do not take even money (the same as taking insurance). Wrong is wrong. If it’s wrong to take insurance (and it is), then it doesn’t matter what your hand is. Insurance has nothing to do with what you’re holding. It is a bet on the dealer’s down card (will it or won’t it be a ten?). You have to understand this.

Multiple-Card Holdings

Obviously, if your hand comprises more than two cards, you can’t double, split, surrender or insure. So, your only decision is whether to hit or stand. For hard hands, follow the same rules as for the two-card holdings, with one exception. There is a fine point concerning 16 vs. 10. It turns out that if your 16 is three or more cards or the result of having split a pair, then it is slightly better to stand than to hit. Knowing this isn’t going to put a lot of extra dollars in your pocket, but it is the correct way to play the hand.

For soft totals, you consider the ace and the total of all the other cards in your hand. For example, A,2,4 is ace-six; A,4,2,3 is ace-nine. And the rules are: always hit ace-six or below; always stand on ace-eight or above; and for ace-seven, stand on dealer’s 2–8, but hit vs. 9, 10 and ace.

In the second part of this article, to appear in next month’s issue, we’ll reprint an interview I did with Henry Tamburin that goes into great detail explaining the finer points of my Ultimate Blackjack Strategy Cards. Until next time, good luck and … good cards!

Editor’s Note: Don Schlesinger is the leading authority when it comes to the game of blackjack. He is a gaming mathematician, author, lecturer, player, and member of the Blackjack Hall of Fame, and his work in the field has spanned more than four decades. He’s probably best known for his book Blackjack Attack: Playing the Pros’ Way and Don Schlesinger’s Ultimate Blackjack Strategy Cards.